How to Build a Kid-Safe Active Transportation Network in San Francisco

KidSafe SF is calling on SFMTA to build a safe, low-stress, All Ages and Abilities mobility network with the Active Communities Plan. This is the first in our series of policy briefs to inform the plan.

Our top recommendations:

The network should consist of Protected Mobility Lanes (Class I and Class IV routes with protected intersections) and Kid-Safe Infrastructure (Slow Streets, Low-Traffic Neighborhoods, and Wiggles)

The city should stop building new routes with sharrows or Class II bike lanes, and upgrade existing routes with these elements to protected or Kid-Safe infrastructure

The SFCTA board should prioritize Prop L funding for projects in the Active Communities Plan, so that the plan can be implemented fully within the next 5 years.

What if San Francisco had a truly connected network of streets designed to allow everyone–kids, seniors, the mobility impaired–to bike and roll safely anywhere within the city? Between the city’s shift to protected bike lanes in the mid-2010s and pandemic-era Slow Streets, there is now a foundation of street safety treatments we know work well to keep people safe.

Yet the city is still moving too slowly to connect this patchwork of safe corridors. 633 people suffered severe or critical injuries from traffic violence requiring care at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital in 2020, the last year for which the city reported data. San Francisco also has a goal of reaching 80% of trips by sustainable modes by 2030, but in the past several years sustainable mode share has been decreasing.

We can’t reach this goal–and by extension our city’s climate goals–without dramatically increasing San Franciscans’ use of bikes, scooters, walking, and other mobility solutions. Numerous studies point to safe, protected infrastructure as the number one factor influencing peoples’ decision to ride a bike in urban environments. Protected mobility infrastructure also increases safety for other road users, decreasing collisions of all kinds. If we want to increase trips by bicycles and scooters, we have to provide a safe, connected, low-stress network of streets that are comfortable for any rider, whether they’re our youngest children, a service worker who just bought a scooter to get home from late shifts, or our most vulnerable seniors.

To achieve this vision, we have to move beyond a piecemeal, street-by-street and block-by-block approach to redesigning our streets and create a citywide plan and framework. That’s where SFMTA’s Active Communities Plan comes in.

For the first time, SFMTA’s Active Communities Plan proposes to make the delivery of a comprehensive bike network within five years official city policy. The plan’s draft “network Northstar goal” calls for the city to:

A safe network that connects schools, parks, commerce, and transit to every part of the city would be a bold, transformative step forward toward building the kid-safe city we need. We’re excited to see the Active Communities Plan set out such an ambitious vision and commit to getting it done within the next five years. We’re committed to helping see that vision become reality, and to holding SFMTA accountable for achieving it.

But long experience has taught us that just putting paint on the ground isn’t enough to create streets safe enough for our kids. And we know that if we make streets safe enough for kids, they’ll be safe for everyone. To truly realize this vision, more work must be done to define the term “safe” in this plan to ensure that we get more than just sharrows, but streets where we aren’t taking our lives in our hands every time we bike or roll to school or work.

Paint alone does not keep people safe on our streets

We all know what isn’t safe. These outdated street designs put our families at risk and should have no place in the Active Communities Plan.

Sharrows

San Francisco was a pioneer in slapping these painted bike arrows onto streets starting in the 90s. Since then, they have proven to be useless for safety, allowing politicians to try to take credit for doing something for cyclists while doing nothing to slow vehicle traffic or provide separation. One study even found painting sharrows to be worse than doing nothing.

Recommendations

Routes with sharrows should be upgraded to include modal filters, traffic diverters or protected bike lanes

Sharrows should be considered as part of a “wayfinding” toolkit of pavement markings for cyclists, not as safety infrastructure that creates low-stress mobility routes

Unprotected bike lanes (“Class II bike lanes”)

Imagine sending your child off to school knowing they’ll be inches away from giant trucks, “protected” from traffic only by a thin strip of white paint on the ground and with no protection at all against opening car doors. This is, of course, not the future our city should be building more of. In addition, we know through hard experience that unprotected bike lanes quickly become magnets for double-parking, which puts cyclists at risk when they must merge into heavy traffic and creates even more chaos and strife on our streets.

Unprotected bike lanes are also the location of “dooring” collisions, which accounted for 291 injury collisions, 72% of which involved bicycles, between 2017 and 2022.

The Plan should build no more of these unsafe designs and upgrade existing instances, with priority to unsafe streets in Equity Priority Neighborhoods, to new, safer street treatments that have already been proven in San Francisco and around the world.

Recommendations

Class II bike lanes in the door zone should be upgraded to protected infrastructure, with priority given to those in Equity Priority Neighborhoods

Class II bike lanes should not be considered acceptable low-stress bicycle infrastructure as part of the Active Communities Plan network

SFMTA should take advantage of recently passed AB 361—which authorizes city vehicles to use automated enforcement to cite vehicles blocking door zone bike lanes—and equip Parking Control vehicles with the technology to automatically issue citations to vehicles blocking the bike lane.

Safe Streets Need Real Protection

Our streets must be safe for people of All Ages, Abilities, and Identities (or AAAI in city planner jargon) to use active transportation. Routes defined in the Active Communities Plan should be:

Protected by physical infrastructure (such as a bike lane on a busy arterial road like San Jose or Townsend St) and/or

Meeting strict legislated targets of low vehicle volumes and low speeds (such as a Slow Street like Cayuga or Page)

SFMTA is already focused on safety outcomes as defined by Vision Zero: How many people are severely injured or killed on our streets each year? The next step is to define the leading indicators of those outcomes, track them, and hold the agency accountable to ensuring that streets on the network meet those target indicators.

The streets that are safest for people on bicycles, scooters, skateboards, and in wheelchairs are those with low speeds and low vehicle volumes and those with protection that minimizes conflict points between cars and people outside of cars. For residential streets, the Slow Streets model allows SFMTA to design a street to meet target speed limits and vehicle volumes, but more work must be done to ensure these targets are met and these streets remain truly slow. On busier streets, people must be protected by robust fully protected infrastructure—including protected intersections— to ensure separation between people on bikes and those in cars.

The following treatments will ensure we’re building infrastructure not just for the most confident and bold among us, but for all San Franciscans

Car-free streets, promenades, cycletracks, and multi-use paths

Removing the hazard is always the best way to ensure safety and low-stress mobility. We’ve gotten to experience the feeling of relief and joy when turning onto JFK Promenade and the Great Walkway. Creating more car-free routes brings us closer to the kid-safe city we need.

Curbside protected bike lanes

Protected lanes for active mobility provide safety, comfort, and low-stress mobility for all who bike and roll and create inviting routes that entice more people to shift trips to active transportation. Different designs—one-directional vs bidirectional, parking-protected, barrier-protected, or curb level bikeways—may fit best on different streets, depending on the number of curb-cuts, direction of traffic, type of building and amount of bicycle traffic.

To be successful and provide meaningful safety, curbside protected bike lanes must be:

Built with robust and durable protection—think precast concrete blocks, not “plastic straws”, aka soft-hit posts.

Continuous, without gaps in protection, difficult merges, or challenging lane changes.

Safe at intersections, with protected intersection designs to ensure that safety doesn’t stop at the crosswalk

Protected intersections

Intersections are the most dangerous collision points for people on bicycles and scooters. Even when bike lanes are protected, intersections often leave vulnerable road users exposed to additional danger from cars. 40% of traffic deaths in San Francisco in 2019 were caused when drivers turned left too quickly and without yielding, and it’s not uncommon for 20% or more of drivers to fail to yield to people cycling at unprotected mixing zones.

San Francisco has built several protected intersections as demonstrations over the past several years, among them 9th and Division, 7th and Townsend, and 5th and Howard. As part of the Active Communities Plan, the city must accelerate protected intersection design and installation on the mobility network, prioritizing streets with the most dangerous intersections and highest bicycle volumes.

Slow Streets that meet safety metrics

Since the COVID pandemic started, Slow Streets have proven their worth as important connectors in the active transportation network. The ability to deploy Slow Streets quickly and at low cost makes them important tools in quickly building out this network across the city. But simply declaring a street to be slow doesn’t make it safe. For Slow Streets to be part of this network, they must:

Meet the SFMTA Board’s established performance standards: average vehicle speeds of less than 15mph and average daily vehicle volumes lower than 1,000. Currently, most of the city’s Slow Streets do not meet the speed standard and several exceed the volume standard, creating streets with too much fast car traffic for any parent to feel comfortable about letting their children ride or scoot. All Slow Streets in the plan must meet the Board’s standards, and bolder treatments (traffic diverters, modal filters, concrete islands, roadway narrowing, chicanes, traffic circles, etc) must be promptly added until these targets are met or exceeded.

Be subject to regular safety re-evaluation, with new treatments put in place if these metrics are exceeded. Metrics should also be improved to incorporate 85th-percentile speed targets and other measures to ensure that Slow Streets aren’t merely slow in name only.

Neighborways, low traffic neighborhoods, and wiggles

While Slow Streets have narrowly focused on residential corridors without Muni routes, a broader set of designs will help bring kid-safe infrastructure to other parts of the city where it’s desperately needed. To be safe and ensure that designs aren’t watered down to meaninglessness, these also must meet rigorous safety metrics for vehicle volumes and speeds. Examples include:

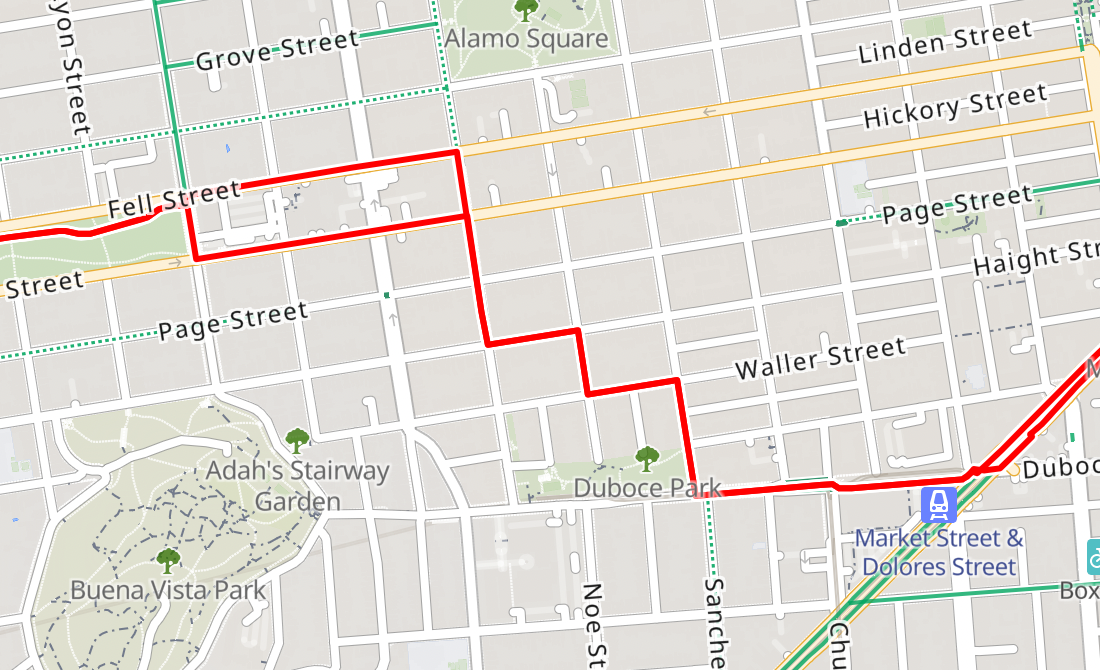

Low traffic neighborhoods, such as the Slow Duboce Triangle vision and superblocks, use a comprehensive traffic diversion and calming strategy to create larger areas safe for all people walking, biking, and rolling, ensuring local vehicle access while redirecting through traffic. These can expand the benefits of Slow Streets to a broader space, but must have safety metrics defined and enforced to ensure they succeed at delivering calm, comfortable streets.

Wiggles. San Francisco’s beloved Wiggle could serve as a template for routes across other hilly areas, but wiggles must be more than painted sharrows to be safe infrastructure. Wiggles should include traffic diversion and calming—again, with performance metrics so we know whether they’re working—to count as “safe” infrastructure for the Active Communities Plan.

Recommendations

All routes defined in the Active Communities Plan should be protected by physical infrastructure (such as a bike lane on a busy arterial road like San Jose or Townsend St) and/or meeting strict legislated targets of low vehicle volumes and low speeds (such as a Slow Street like Cayuga or Page).

If Slow Streets in the plan are not meeting targets, they must be upgraded with physical infrastructure—such as traffic diverters, modal filters, concrete islands, mid-block pinchpoints, roadway narrowing, chicanes, or traffic circles—until targets are met.

New design typologies should be implemented across the network to create safer streets and intersections, such as Low-Traffic Neighborhoods, Wiggles, and Protected Intersections.

Next steps for the Active Communities Plan

Last year, 420 crashes involving cyclists were reported, with countless more missing from official statistics. We know what’s needed to keep us, and our kids, safe on our streets, and we need to see commitments to know that the Active Communities Plan’s talk of safety is more than an idle promise.

We hope the SFMTA Board will join us in:

Celebrating and endorsing staff’s vision for building a complete, well-connected, safe, active transportation network that reaches across the entire city to put all of San Francisco within a quarter-mile of safe infrastructure

Calling for 100% of Active Communities Plan facilities to be truly safe for All Ages, Abilities, and Identities, with no new sharrows or unprotected bike lanes included in the plan and priority given to upgrading the most dangerous existing ones to safe designs

Holding the agency accountable to deliver this plan in the next five years. This cannot become another nice looking vision that sits on the shelf; we must find new, faster ways of delivering street safety projects and see steady progress toward completing construction of the plan during each of the five years.

To help accelerate completion of the Active Communities Plan’s construction, the SFCTA board should:

Ensure Proposition L funds are dedicated to prioritize the rapid rollout of Active Communities Plan infrastructure and programs necessary to complete the full safe network within five years that reaches within a quarter-mile of everyone in the city, with a special emphasis on quickly completing routes to schools